| THE LADDER of MONKS by Guigo II (1140-1193) Epistola de Vita Contemplativa (Scala Claustralium) A Carthusian enters the Grand Chartreuse, The Belles Heures of John Duke of Berry, 1408 fol 97. |

tr. L. Dysinger, based on tr. by J. Walsh and E. Colledge, (Image, N.Y., 1978) pp. 81-89

Latin text in S.C. 163 (Paris, 1970) pp. 82-123

Latin text in S.C. 163 (Paris, 1970) pp. 82-123

II. CONCERNING the FOUR RUNGS [of the Ladder] | II DE QUATUOR GRADIBUS |

ONE DAY while I was occupied with manual labor | Cum die quadam corporali manuum labore occupatus |

I began to reflect on man’s spiritual work, | de spiritali hominis exercitio cogitare coepissem, |

and suddenly four steps for the soul came into my reflection: | quatuor spiritales gradus animo cogitanti se subito obtulerunt |

reading, meditation, prayer, [and] contemplation | lectio scilicet meditatio, oratio contemplatio |

THIS is a ladder for monks (lit.“the cloistered”) Haec est scala claustralium by means of which they are raised up from earth to heaven qua de terra in coelum sublevantur, It has [only a] few separate rungs, yet its length is immense and incredible: gradibus quidem distincta paucis, immensae tamen et incredibilis magnitudinis, |  The Divine Comedy, Paradiso, “Peter Damien at the ladder of heaven” Oxford, Bodl. MS.Holkh. misc.48, p.139 |

for its lower part stands on the earth, | cujus extrema pars terrae innixa est, |

while its higher [part] pierces the clouds and touches the secrets of heaven. | superior vero nubes penetrat et coelorum secreta rimatur |

JUST as its rungs have various names and numbers, | Hi gradus sicut nominibus et numero sunt diversi |

so also so they differ in order and merit; | ita ordine et merito sunt distincti; |

| and if one diligently searches out their properties and functions | quorum proprietates et officia, |

- what each [rung] does in relation to us, how they differ from one another and how they are ranked- | quid singuli circa nos efficiant, quomodo inter se differant et praeemineant, si quis diligenter inspiciat, |

he will regard whatever labor and study he expends as brief and simple compared with the great usefulness and sweetness [he gains]. | quidquid laboris et studii impenderit in eis breve reputabit et facile prae utilitatis et dulcedinis magnitudine. |

Reading is careful study of [Sacred] Scripture, | Est autem lectio sedula scriptuaru |

with the soul’s [whole] attention: | cum animi intentione inspectio. |

Meditation is the studious action of the mind | Meditatio est studiosa mentis actio, |

to investigate hidden truth, led by one’s own reason. | occultae veritatis notitiam ductu propriae rationis investigans. |

Prayer is the heart’s devoted attending to God, | Oratio est devota cordis in Deum intentio |

so that evil may be removed | pro malis removendis |

and good may be obtained. | vel bonis adipiscendis. |

Contemplation is the mind suspended -somehow elevated above itself - in God | Contemplatio est mentis in Deum suspensae quaedam supra se elevatio |

so that it tastes the joys of everlasting sweetness. | eternae dulcedinis gaudia degustans |

HAVING assigned descriptions to each of the four rungs, | Assignatus ergo quatuor graduum descriptionibus, |

we must see what their functions are in relation to us. | restat ut eorum circa nos officia videamus. |

III THE FUNCTIONS of THESE AFOREMENTIONED RUNGS | III QUAE SUNT OFFICIA PRAEDICTORUM GRADUUM |

FOR the sweetness of a blessed life: | Beatae vitae dulcedinem |

Reading seeks; | lectio inquirit, |

meditation finds; | meditatio invenit, |

prayer asks; | oratio postulat, |

contemplation tastes. | contemplatio degustat |

Reading, so to speak, puts food solid in the mouth, | Lectio quasi solidum cibum ori apponit, |

meditation chews and breaks it, | meditatio masticat et frangit |

prayer attains its savor, | oratio saporem acquirit, |

contemplation is itself the sweetness that rejoices and refreshes. | contemplatio est ipsa dulcedo quae jocundat et reficit. |

Reading concerns the surface, | Lectio in cortice, |

meditation concerns the depth | meditatio in adipe, |

prayer concerns request for what is desired, | oratio in desiderii postulatione, |

contemplation concerns delight in discovered sweetness. | contemplatio in adeptae dulcedinis delectatione. |

IX HOW GRACE is HIDDEN IX DE GRATIAE OCCULTATIONE |  |

O MY soul, too long have we prolonged this speech. Yet it was good for us to be here, and with Peter and John to contemplate the glory of the spouse; and to abide for a time with Him, had He wished us to make here not two, not three tabernacles, but one in which we might dwell together, and together be filled with joy. | O anima, diu protraximus sermonem istum. Bonum enim erat nos hic esse et cum Petro et cum Johanne contemplari gloriam sponsi et diu manere cum illo, si vellet hic fieri non duo, non tria tabernacula, sed unum in quo simul essemus, simul delectaremur. |

| BUT now the spouse says, “Let me go, for dawn is now arising,” now you have received the light of grace and the visitation which you desired. Sed jam, dicit sponsus, dimitte me, jam enim ascendit aurora, jam lumen gratiae et visitationem quam desiderabas accepisti. |  |

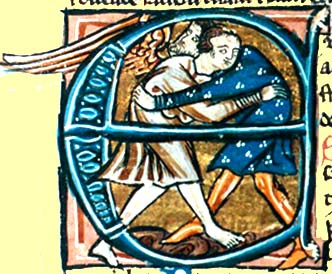

HE thus gives his blessing, He withers the nerve of the thigh, He changes the name of Jacob to Israel; and then for a brief time He withdraws, this spouse so long desired, so quickly gone. Data ergo benedictione et mortificato nervo femorum et mutato nomine de Jacob in Israel, paulisper secedit sponsus diu desideratus, cito elapsus. |  Jacob Wrestles with the Angel, 12th c. illum MS |

HE removes himself, thus ending, too, [our] visitation, and the sweetness of contemplation; | Subtrahit se quantum ad praedictam visitationem, quantum ad contemplationis dulcedinem; |

but yet His presence abides [with us]: thus guiding [us]; thus giving [us] grace; thus uniting [us to Himself]. | manet tamen praesens quantum ad gubernationem, quantum ad gratiam, quantum ad unionem. |

XII RECAPITULATION | XII RECAPITULATIO PRAEDICTORUM |

IN order to focus more clearly what we have already said at length, we will gather it into a summary. In what was said above it has been shown through examples how these three rungs interrelate with each other, and how they precede one another another in both the orders of time and causality. | Ut ergo quae diffusius dicta sunt simul juncta melius videantur, praedictorum summam recapitulando colligamus. Sicut in praemissis praenotatum est exemplis, videre potes quomodo praedicti gradus sibi invicem cohaereant; et sicut temporaliter, ita est causaliter se praecedant. |

Reading, like a foundation, comes first: and by giving us the matter for meditation, it sends us on to meditation. | Lectio est enim quasi fundamentum prima occurrit, et data materia mittit nos ad meditationem. |

Meditation diligently investigates what is to be sought; it digs, so to speak, for treasure which it [then] finds and exposes: but since it is of itself powerless to obtain it, it sends us on to prayer. | Meditatio quid appetendum sit diligentius inquirit, et quasi effodiens thesaurum invenit et ostendit; sed cum per se obtenere non valeat, mittit nos ad orationem. |

Prayer, lifting itself with its whole strength to God, pleads for the desired treasure - the sweetness of contemplation. | Oratio se totis viribus ad Deum erigens, impetrat thesaurum desiderabilem, contemplationis suavitatem. |

[Contemplation’s] advent rewards the labors of the other three; it inebriates the thirsty soul with the sweetness of heavenly dew. | Haec adveniens praedictorum trium laborem remunerat, dum coelestis rore dulcedinis animam sitientem inebriat. |

Reading accords with exercise of the outward [senses]; meditation accords with interior understanding; prayer accords with desire; contemplation is above all senses. | Lectio est secundum exterius exercitium, meditatio secundum interiorem intellectum, oratio secundum desiderium, contemplatio supra omnem sensum. |

The first degree pertains to beginners, The second to the proficient, the third to devotees, the fourth to the blessed. | Primus gradus est incipientium, secundus proficientium, tertius devotorum, quartus beatorum. |

see also: Catholic Notebook

This Webpage was created for a workshop held at Saint Andrew's Abbey, Valyermo, California in 1998